The Product Leader’s Guide to Balancing Product Discovery and Product Delivery

In my new book STRONG Product People: A Complete Guide to Developing Great Product Managers, I’ve aimed to deliver everything a product leader needs to help team members live up to their full potential and to feel empowered. Get a quick overview of the book here and find out how I recommend approaching the content in the book here.

Want to actually dive into some of the book content? In this post, you can preview Chapter 17: Balancing Product Discovery and Product Delivery.

In every product organization, you as HoP—along with your product managers—must constantly balance product discovery (what to build) and product delivery (build it). Do too much of the former, and you’ll never get anything built. Do too much of the latter, and you’ll fall victim to building the wrong products in a beautiful way.

Even the most-senior PMs are in an ongoing struggle to balance the “forces of evil.” First, they must prevent feature creep and constantly say no to things that don’t move the needle on their goals/KPIs or that don’t have a significant impact on the lives of their users. Second, they have to make sure they have enough time to do some deep thinking, which means not sitting in 15 meetings every day. And, finally, they have to be sure that they aren’t feeding the beast, that is, that they aren’t handing developers random tasks simply because they are waiting and the PM has run out of meaningful work in the backlog.

Even the most-senior PMs are in an ongoing struggle to balance the “forces of evil.” - Tweet This

As HoP, you’ll need to provide your junior/associate PMs with guidance to make sure they don’t fall into one of these traps. But even your more experienced PMs may sometimes fail to get the mix of product discovery and product delivery right, so you’ll need to keep an eye on everyone in your organization—not just the juniors.

Keep in mind that there’s really no right or wrong here, so long as you’re not operating at the extremes. It’s all about getting the mix right, and that will depend on your organization, your people, and the products you are building. But keep this one thing in mind: making sure you are building the right things is far more important than just building things. Or, as our good friend Albert Einstein (every tech book needs a good Einstein quote, right?) reportedly said, “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

“Making sure you are building the right things is far more important than just building things.” - Tweet This

I have found that a particularly effective way to check in with PMs is to ask them to reflect on how they are balancing discovery and delivery in their day, week, month, and quarter. Task boards are also an important tool for finding and maintaining this balance. In this chapter, I consider each of these approaches. Note that I will be using the PMwheel buckets to discuss the different PM activities.

Figure 17-1 The PMwheel buckets

Get Your Day Right

For your PMs, getting your day right is the first and easiest part of balancing product discovery and product delivery. Ask your PMs to reflect on whether or not they have enough time to do deep thinking and learning, conduct user interviews, research data, develop new hypotheses, have brainstorming meetings with their team, and so on. These are all things related to PMwheel buckets 1, 2, 3, and 5, which usually require larger chunks of uninterrupted time.

Doing this right means not getting stuck in meetings all day long. As I show in Figure 17-2, the right balance is approximately 50 percent discovery and 50 percent delivery. It’s not so important what exactly you are doing each day so long as you have set aside maker time that is used mainly for discovery-related tasks.

“It’s not so important what exactly you are doing each day so long as you have set aside maker time that is used mainly for discovery-related tasks.” - Tweet This

Figure 17-2 Getting your day right

Get Your Week Right

To determine whether or not your PMs are getting their week right, first ask them to review the previous six weeks on their calendar. Then consider the following guidelines with them:

Are they getting in touch with the customer every week? If not, encourage your PMs to block out time in their schedules for this essential task or offer to help remove the obstacles that prevent them from doing so. I personally insist on one customer/user touchpoint each week. This can simply be a “listen-and-learn” activity such as reading some app-store reviews or a quick call to two or three of your loyal customers to ask them what they think about your latest release.

Are they looking at user data to refine existing assumptions or create new ones? At least once a week, PMs should see how people are using the product. By doing this, they can come up with new ideas/assumptions to work on.

Are they looking at their success metrics and progress on their goals? And at least once a week, every PM should also look at how they are performing against their current success metrics. How are your products performing? Are people using them like they are supposed to use them, and is everything going well on the revenue side of the business?

Are they spending time with their team? How many hours a week is the PM sitting at her desk in the team space and available for questions asked by developers, designers, and other team members? And are they also engaging in other team-related activities, such as the occasional table tennis match or after-work get-together?

Are they reviewing and adjusting their short- and midterm planning? Every week, PMs should also check in on their short- and midterm planning. How is the current iteration/sprint going? Will we ship what we hope to ship? How are our experiments going, what are the next most important experiments to conduct, and is there enough time to do them? If not, how will this affect my overall planning and roadmap, along with stakeholder and customer communication?

All this can be a challenge to balance. However, by using product management task boards (covered later in this chapter), PMs and their teams can be easily reminded of what they should do to get the week, month, and sometimes even the quarter right.

Get Your Month Right

To get the month right, there are a series of questions I personally like to ask my own PMs:

Is there meaningful work on the development backlog? (Meaningful for the user, the company, and the team)

Is there some improvement in the life of your user this month? If not, why not?

What do PMs want to learn this month about their users or their team that they don’t know now?

Is there a way to improve their discovery work to learn faster and/or to improve the quality (the things that get coded have more potential than the month before) of the discovery?

How many ideas can move to the ideas trashcan this month? (I’ll explain this in detail in the task boards section below)

Are we accumulating tech dept for the sake of finishing new features earlier? If yes, how can we make sure we get back to a healthy balance?

Get Your Quarter Right

To ensure that product discovery and product delivery are balanced, it’s also important for PMs to get their quarter right. I have found the following three exercises to be particularly helpful in doing this.

Draw the quarter. Ask your PMs to reflect on how much time they want to devote to “understanding the problem” versus “getting it done (with their dev team)” versus any of the eight PMwheel buckets. Make sure these different areas are in some sort of balance. Figure 17-3 is an example of how you can draw the quarter using eight PMwheel buckets.

Figure 17-3 Draw the quarter using the eight PMwheel buckets. More “understand the problem” and “do some planning” at the end of the quarter to prepare for the next one.

Plan the quarter. PMs engage in a variety of repetitive activities every quarter. Help your PMs remember to start them early enough and to set aside enough time for them. More specifically…

Check your product strategy—is it still on a solid foundation? Does it help your PMs decide what to do? If not, then plan to refine it.

Collect (if necessary) and review open ideas, then plan bigger opportunity assessments

Set goals. If you are doing OKRs, review and set your objectives and agree on key results and metrics.

Beware the sand (we’ll discuss the rock, pebbles, sand time-management framework in the next chapter). Collect the little things—reserve time for them but don’t really plan them. You’ll end up doing other little things.

Make sure PMs ask their team whether or not the tech stack needs an update

Do a reality check. Once there’s a plan in place, ask your PMs to do a reality check. More specifically…

Check staffing levels—what’s the availability of the team? Do all calculations on person-days minus holidays, conferences, all-hands meetings, and other activities that take them away from the team. This is always an eye-opener for everyone involved in the planning process. Ask your PMs to check again if there is enough time for discovery-related tasks.

Make assumptions on your throughput—how many large, medium, and small tasks can the team deliver?

Make sure your PMs won’t keep getting too busy at the end—plans should be challenging but not overly ambitious. Constantly falling short does not feel good!

Product Management Task Boards

As I mentioned earlier in this chapter, project management task boards and the related standups can help PMs and their teams be reminded of what they should do to get the week, month, and their quarter right. A task board is simply a way to visually depict work at various stages of a process using cards to represent work items and columns to represent each stage of the process. Cards are moved from left to right on the board to show progress and help teams coordinate their work with one another, as shown in Figure 17-4.

Figure 17-4 A simple task board

Task boards can be simple or complex. Simple boards have columns for open, in progress, and completed—or to-do, doing, and done. Complex boards start there but subdivide in-progress work into multiple columns so that work across an entire value stream can be more easily visualized. Each board usually also comes with its own standup meeting where team members update one another on progress—and obstacles that are blocking progress—and move the cards. These standup meetings are usually conducted weekly.

Depending on the size of the organization, it’s useful to create task boards with different levels of detail and focus. These range from a high-level idea board, to an overall product board, down to a product discovery board, to a development team board. Let’s consider each in turn.

Idea Board

An idea board visualizes the flow of an idea or assumption from the point that someone has it to the point when the idea becomes a qualified opportunity to the point where it is assigned to a PM or team for next steps. Figure 17-5 shows the flow of this board.

Figure 17-5 An idea board - do we see enough potential?

Product Overview Board

This board visualizes high-level product initiatives and their current status, and it is most helpful to you as HoP. The cards on this board make their way from being qualified opportunities, through product discovery, to the implementation phase (in delivery), on to the really important and often forgotten phase of validation and incremental improvements, and finally to the sunsetting phase—when obsolete features get first hidden, then buried, then developers delete their code. If an idea doesn’t survive the discovery phase, it’s moved directly into the trashcan. Figure 17-6 shows the flow of this board.

Figure 17-6 A product overview board

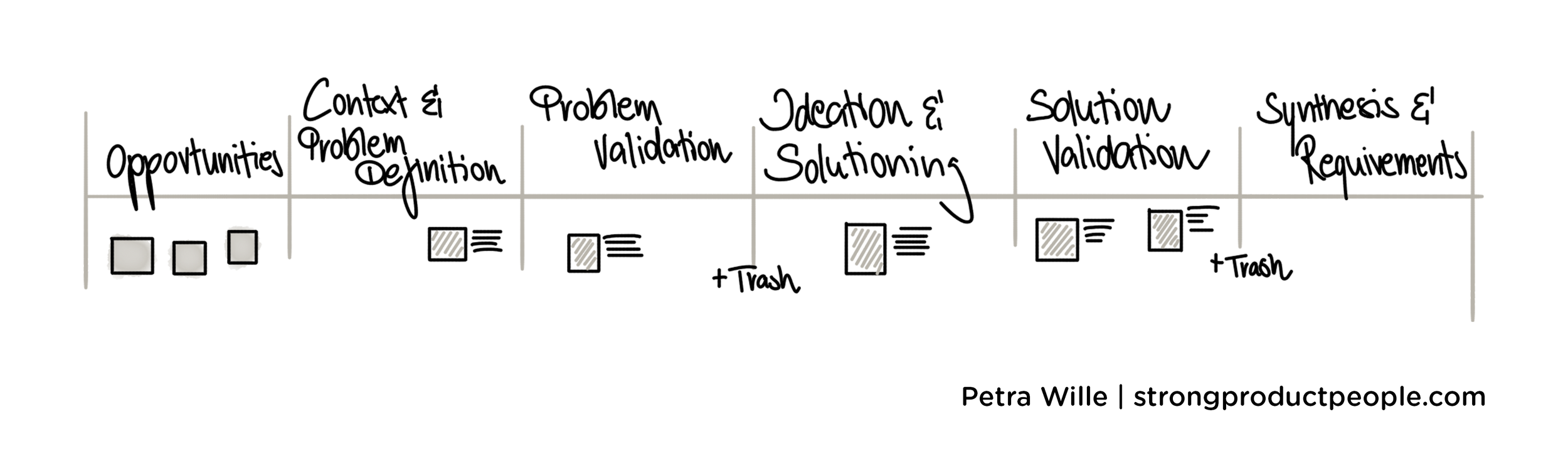

Product Discovery Board

The product discovery board visualizes all the activities you need to do to create a valuable, usable, feasible, and viable product. The board is owned by your PM and the related standup meeting usually involves all the people invested in this process—most often, the PM, the designer, and at least one engineer. (Some call this the “holy trio” or “product trio.”) But it can also include data analysts or interested stakeholders who just want to stay informed. Figure 17-7 shows the flow of this board.

Figure 17-7 A product discovery board

Product Delivery Board

This is the task board for the development team. It’s usually owned by the team and most companies I see these days are pretty good at creating product delivery boards that really help them get their work done. I have found it helpful if PMs insist on the validation column at the end of the process to make sure everyone is aware of the fact that “done and released” doesn’t mean we are not touching this again. There is a lot of value in iterating on a feature based on the learnings you are making once something is released and used by your users!

And there is also a lot of value in getting rid of things that just don’t take off as expected. That’s what the trashcan is for. But please—if things are routinely ending up in this trashcan, then refine your discovery process and make sure this happens less often. Writing code to implement something that doesn’t work in the end is the most expensive mistake a company can make! Figure 17-8 shows the flow of this board.

Figure 17-8 A product delivery board

Figure 17-9 A summary of all four product management task boards

How Boards Help Keep the Balance

Keeping the balance between product discovery and product delivery always requires you to make sure you know what to balance. And this is only possible if there is some kind of a written/visible representation of the activities you need to balance. Task boards help to do exactly that. They are a visual representation of your workflows and of all the tasks assigned to each of the steps of the flow.

If, for example, one of your PMs is doing a lot of “solution hypothesis” work but forgets to understand and validate the underlying problems, a task board can remind them of these essential steps. It’s a friendly reminder of what the PM and her team have agreed on as their ideal workflow to balance things.

In addition, the rhythm of adding, moving, and finishing work items to the board helps everybody balance their own workload and more readily see hiccups in the process. Are tasks stuck in one of the columns for a long time? Why is this? Is the board starting to get empty and there are few open tasks? Then it’s probably time to find new work, opportunities, experiments, and backlog items.

Both things—a workflow that is focused on balancing forces, and the fact that the board visualizes shortcomings of this workflow—help PMs and teams to keep the balance without thinking about it every minute of their day. This is a liberating structure.

Further Reading

Jeff Patton’s take on finding the right balance—Balancing Continuous Discovery and Delivery

https://aycl.uie.com/virtual_seminars/pmux_balancing_continuous_discovery_and_deliveryHow Much Time Should You Spend in Product Discovery? by Teresa Torres

https://www.producttalk.org/2018/04/time-in-product-discovery/Fix Delivery to Make Time for Discovery by Teresa Torres

https://www.producttalk.org/2015/03/fix-delivery-to-make-time-for-discovery/Product Discovery in the Multitrack of Madness by Lucio Santana

https://medium.com/swlh/product-discovery-in-the-multitrack-of-madness-cfe8632f1962

Buy the Book

In addition to Balancing Product Discovery and Product Delivery, you’ll find plenty more chapters in the book, written to help you understand:

Why you need to focus on the personal development of every product manager—and of the team as a whole—to unlock their full potential

Why coaching is an important part of your job, and how to do it in the most effective way

How you can define what a good product manager looks like

How you can accurately assess product managers and provide them with valuable, actionable, and helpful feedback on their current performance that will help them perform even better

Which methods/frameworks you can use to make sure product managers learn what they need to know to be more effective—enhancing their people skills

The book will also help you to:

Reflect on your own coaching personality and define your own areas for development

Efficiently prepare and use one-on-ones as your main coaching tool

To get your hands on a copy, head here to buy the book today.